“The Entire Collection Could Have Been Held by a Four-Shelf Bookcase”: Dr. John Shaw Billings and the Surgeon General Office’s Library

16 May 2019 by Grayson Van Beuren

Eight Centuries | 19th Century | American Studies | History | History of Science | New Collections

We recently augmented 19th Century Masterfile with data from the Index-Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon-General’s Office. This index—and the library that spawned it—were largely the work of one incredible surgeon and bibliophile: Dr. John Shaw Billings.

We’ve all, while researching, thought to ourselves, “I sure wish the library had this particular book,” or lamented, “It sure would be great if this library’s collection was more substantial in my research area.” But has a frustrating research experience ever bent the trajectory of your life and career towards fixing those frustrations?

The answer was “yes” in the case of Dr. John Shaw Billings.

Dr. Billings was an odd mixture: a remarkable medical practitioner and a librarian. As a student working on his doctoral thesis, he had struggled to find the sources he needed in the limited medical libraries of the United States. So what did he do? He devoted his career to augmenting the Library of the Surgeon-General’s Office so that by the time he retired in 1895 it had grown into a world-renowned research collection. The library eventually formed the basis of the National Library of Medicine.

Not content to let the Surgeon General Library be his only legacy, Billings also played a crucial role in the early years of the New York Public Library and helped IBM-founder Herman Hollerith integrate machine-driven statistics into the United States Census. This is his story.

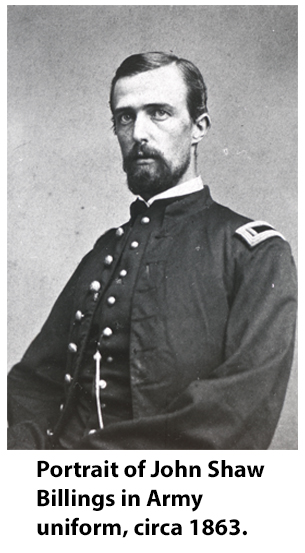

John Shaw Billings was something of a phenom. Born in 1838 on the then-frontier of Indiana, he consumed books voraciously as a child. By age ten, he was well-versed in Plutarch, Bunyan, and James Fenimore Cooper. 1 He’d learned Latin and Greek by the time he was a teenager, and in 1852—when he was only 14—Billings began his studies at Miami University in Ohio. He absorbed higher education at a remarkable rate. In 1858 he began studying medicine at the Medical College of Ohio, receiving his medical doctorate in 1860 when he was 22.2

…the United States utterly lacked a comprehensive medical library.

Medical school opened an unexpected door for Billings. While performing research for his dissertation on the treatment of epilepsy, he learned that the United States utterly lacked a comprehensive medical library.3 Plenty of smaller libraries existed—Billings travelled from Ohio to Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York to compile his bibliography—but there existed no comprehensive medical library providing access to consolidated source material on a given subject.4 This nagging issue remained in the young doctor’s mind as he entered the medical profession.

It took some time for Billings to attain a position where he could address this issue. The Civil War broke out a year after he gained his doctorate and Dr. Billings answered the subsequent call for surgeons, joining the Union Army in 1861. He served as a field surgeon until 1863 and during this this time saw action at the horribly bloody battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. Billings spent part of 1864 in convalescence recovering from the trauma and strain of wartime medicine.5

It took some time for Billings to attain a position where he could address this issue. The Civil War broke out a year after he gained his doctorate and Dr. Billings answered the subsequent call for surgeons, joining the Union Army in 1861. He served as a field surgeon until 1863 and during this this time saw action at the horribly bloody battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. Billings spent part of 1864 in convalescence recovering from the trauma and strain of wartime medicine.5

His Army superiors realizing he needed a change-of-pace, Billings was assigned to the Surgeon General’s Office in Washington in December 1864. Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes initially put Billings in charge of managing the many civilian physicians brought in to help with the war effort. With the war’s end in 1865, focus in the department shifted. In October of that year Barnes moved Billings to manage the office’s reference library.6

The collection that Billings inherited was, in a word, paltry. The Library of the Surgeon General’s Office began in 1836 as an informal repository of medical texts kept by the U.S. Army Surgeon General. The first request for funds to stock the library in 1836 amounted to only 150 dollars, a small amount even for the time.7 Four years later in 1840, the library had hardly grown beyond its original scope. Its size was illustrated by historian Wyndham Miles in his 1982 history of the National Library of Medicine:

The entire collection could have been held by a four-shelf bookcase, shoulder high and 7 or 8 feet wide.8

By 1862 the library still only comprised roughly 2,100 volumes. When Billings was made manager of the library in 1865, it had only grown to 2,282 physical volumes (representing 602 individual titles).9 In contrast, the medical research library at the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia had contained 3,400 titles thirty years earlier in 1830, and many individual physicians’ libraries were comparable or larger than the Surgeon General Office’s Library.10

The library that Billings inherited was, in a word, paltry.

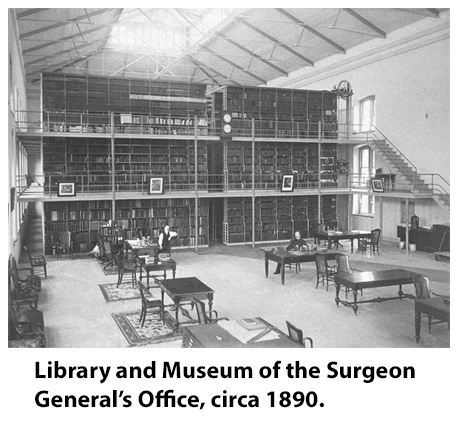

Billings attended to his job studiously. He ultimately stayed with the library for thirty years, from 1865 until his retirement from the army in 1895. During this time the library’s collection grew rapidly. By 1873 the library housed 25,000 books and 15,000 medical pamphlets. By 1880, it included 50,000 books and 60,000 pamphlets. In 1895—the year Billings retired—the Surgeon General Office’s Library housed a total 116,787 books and 191,598 pamphlets. It was the largest medical library in the world.11

This growth was achieved in spite of the pitifully small budget allocated to collection management—“a government organization run on a shoestring” in the words of medical historian William Bean.12 Billings became a master of squeezing each penny for maximum effectiveness. He developed personal relationships with book dealers, bid on books himself at auction, and impressed on his agents the importance of acquiring volumes at as cheap a price as possible. Billings especially advocated buying books secondhand, provided they be “not much damaged.”13 He left few options unexplored when searching for additions to the library, even going so far as to request diplomats in the State Department bring back foreign volumes from their travels.14

This growth was achieved in spite of the pitifully small budget allocated to collection management—“a government organization run on a shoestring” in the words of medical historian William Bean.12 Billings became a master of squeezing each penny for maximum effectiveness. He developed personal relationships with book dealers, bid on books himself at auction, and impressed on his agents the importance of acquiring volumes at as cheap a price as possible. Billings especially advocated buying books secondhand, provided they be “not much damaged.”13 He left few options unexplored when searching for additions to the library, even going so far as to request diplomats in the State Department bring back foreign volumes from their travels.14

Big or small, a research library is only as useful as its catalog. Billings knew this lesson well, and in 1873 he began work on a new index to his growing library: the Index-Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon-General's Office.15 The first volume of the first Index-Catalogue “series” appeared in 1880 and Billings continued to publish volumes until 1895, producing sixteen in total.16 The publication continued long after Billings left the library: four more series appeared until 1961, when the Index-Catalogue was finally discontinued after the publication of sixty-one volumes.17

Billings became a master of squeezing each penny for maximum effectiveness.

In addition to the Index-Catalogue—which was essentially only a shelflist of the library—Billings started one of the first indexes of contemporary medical publications: the Index Medicus. Begun in 1879, the Index Medicus was a monthly catalog of periodical publications across the entire spectrum of medical fields.18 Subject-based cataloging of new bibliographic material made the Index Medicus a revelation in the medical field, and current-day services like MEDLINE and PubMed owe much to this early indexing pioneer.19 Technology has changed since the late nineteenth century, but the spirit and purpose of information dissemination remains the same.

Beyond the library sphere, Billings had ties to inventor Herman Hollerith who would later go on to found the Tabulating Machine Company, the direct predecessor to IBM. Acting as a consultant to the 1880 and 1890 United States Censuses, Billings helped Hollerith conceive and implement a punch card system that automated the collection of population statistics.20 The results of his work with Herman—i.e., the idea that the Census can be more than a simple population count—is borne out every ten years, with each successive Census collecting more and better statistical information.

Beyond the library sphere, Billings had ties to inventor Herman Hollerith who would later go on to found the Tabulating Machine Company, the direct predecessor to IBM. Acting as a consultant to the 1880 and 1890 United States Censuses, Billings helped Hollerith conceive and implement a punch card system that automated the collection of population statistics.20 The results of his work with Herman—i.e., the idea that the Census can be more than a simple population count—is borne out every ten years, with each successive Census collecting more and better statistical information.

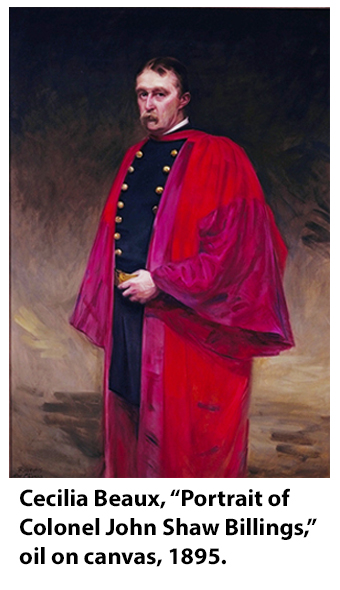

Finally, Billings’s contributions did not end after he retired from the Surgeon General’s Office Library in 1895. That year he was asked to serve as the executive director in charge of the newly-consolidated New York Public Library system.21 This position became a second career for Billings, and he remained in the role until his death seventeen years later in 1913.22

The success of his work for the NYPL is evident in the strength of the institution as it exists today. As of 2016, the library system boasts a staggering 46.3 million research materials, making it one of the largest research libraries in the United States.23

* * *

Dr. Billings’s legacy was remarkable and multifarious, but the Surgeon General’s Office Library remains his crowning achievement. It was renamed the Army Medical Library in 1922, and in 1956 it formed the basis of the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s collection. Dr. Billings’s portrait hangs in the main reading room of that institution to this day.24

Users of 19th Century Masterfile: 1106 – 1930 can access all entries that appeared in the five series of the Index-Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon-General’s Office. Check your institution’s database subscriptions to find if you have access to 19th Century Masterfile, or sign up for a free trial at https://public.paratext.com/customer/.

[1] Melanie Modlin, “Twelve Things You Probably Didn’t Know About John Shaw Billings,” NLM in Focus, April 12, 2017, https://infocus.nlm.nih.gov/2017/04/12/twelve-things-you-probably-didnt-know-about-john-shaw-billings/; Robert A. Kyle, David P. Steensma, “John Shaw Billings: Civil War Surgeon, Medical Librarian, Founder of Index Medicus, and First Director of the New York Public Library,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 94, Issue 3, March 2019, p. e45 – e46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.023.

[2] Modlin, “Twelve Things.”

[3] National Library of Medicine: John Shaw Billings Centennial (Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, 1965), 5.

[4] Kyle and Steensma, p. e45 – e46.

[5] Modlin, “Twelve Things.”

[6] Wyndham D. Miles, A History of the National Library of Medicine: The Nation's Treasury of Medical Knowledge (Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, 1982), 25.

[7] “A Brief History of NLM.”

[8] Miles, 6.

[9] “A Brief History of NLM”; Miles, 20.

[10] Miles, 6.

[11] “A Brief History of NLM”; “About Index-Catalogue,” U.S. National Library of Medicine website, accessed May 6, 2019, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/indexcat/abouticatalogue.html.

[12] Modlin, “Twelve Things.”

[13] Miles, 30 – 31.

[14] “A Brief History of NLM.”

[15] John Shaw Billings, preface to Index-Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon-General's Office, United States Army, Authors and Subjects, Vol. I. A—Berlinski (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880), iv – v.

[16] Laurence F. Schmeckebier and Roy B. Eastin, Government Publications and Their Use, 2nd rev. ed. (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1969), 86 – 87.

[17] John Shaw Billings Centennial, 5.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “A Brief History of NLM”; John B. Blake, “Billings and Before: Nineteenth Century Medical Bibliography” in Centenary of Index Medicus: 1879-1979, (Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, 1980), 38.

[20] Kyle and Steensma, e45 – e46.

[21] For more information on the fascinating history and current-day mission of the NYPL, see our blog post on the subject. Harry Miller Lydenberg, History of the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, (New York: New York Public Library, 1923), 350 – 352.

[22] Lydenberg, 352.

[23] “The New York Public Library: At a Glance,” (New York: New York Public Library, 2016).

[24] “A Brief History of NLM.”

Popular Posts

- "A Profitable, Elevating, and Attractive Profession”: Bettering Farming through the Farmers' Bulletin

- The Granite Monthly in 19th Century Masterfile

- A Smell Bad Enough to Leave Town: One of the Worst Odors in the History of Science

- A Fish Woman, a Cyprian Noble, and a Punk Rocker Couple Walk into a Bar: Narratives of Human Experience in Europeana

- Modifications to Reference Universe for Web and Public Service Administrators

Categories

- News

- Product Updates

- New Collections

- bird

- 8C Product Updates

- USM Product Updates

- RU Product Updates

- Reference Universe

- Eight Centuries

- United States Masterfile

- 17th Century

- 18th Century

- 19th Century

- 20th Century

- 21st Century

- American Studies

- European Studies

- History

- Art History

- History of Mathematics

- History of Science

- Political History

- Literature

- Philosophy